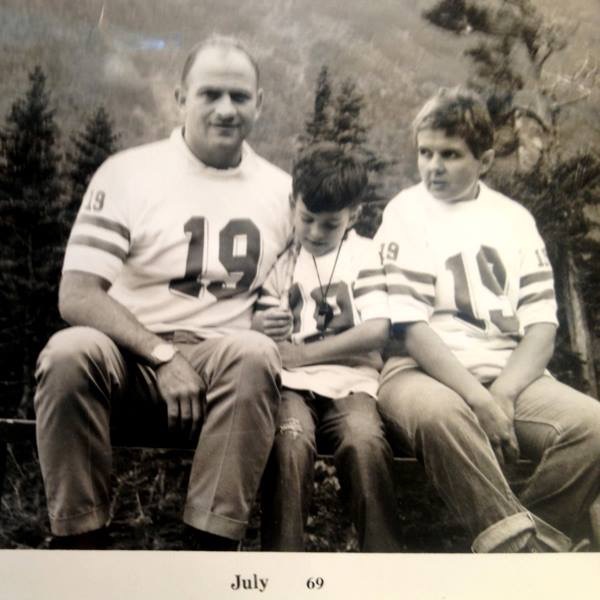

The author and his parents at Hojo’s in 1969 sporting their cotton sweatshirts and dungarees.

It’s surprising what we can get away with…

People get into trouble in the mountains for various reasons: groups split up, people get lost, weather overtakes folks, they suffer an injury, they get wet and cold, become hypothermic and stop thinking clearly, et cetera, et cetera. Suffering an injury is unavoidable. We can be very careful and take precautions, but accidents happen. The rest is obviously avoidable by simply hiking with others and staying together, using a map, using one’s head, observing the weather and knowing the forecast, and bringing the right gear.

Well, maybe that last one isn’t so obvious. So let’s talk about gear.

Gearing Up: Fast and Light or Slow and Heavy? THAT is the Question

So let’s talk about this. What’s needed? Really needed. It’s surprising what we can get away with.

Do we pack light foregoing many potentially important items but feeling less encumbered, or do we pack it all — a 24-hour pack — comfortable with the knowledge that we’re prepared for whatever the day (or saga) brings? It’s a question we all ask ourselves as hikers. Usually on an on-going basis as we learn, develop, and adapt. It can also be a hot-button topic in the hiking community; we constantly hear about and criticisms of people that aren’t prepared getting into trouble in the mountains. It’s pretty much a weekly thing during the warmer months since more inexperienced people venture forth during that time.

Do we pack light foregoing many potentially important items but feeling less encumbered, or do we pack it all — a 24-hour pack — comfortable with the knowledge that we’re prepared for whatever the day (or saga) brings? It’s a question we all ask ourselves as hikers. Usually on an on-going basis as we learn, develop, and adapt. It can also be a hot-button topic in the hiking community; we constantly hear about and criticisms of people that aren’t prepared getting into trouble in the mountains. It’s pretty much a weekly thing during the warmer months since more inexperienced people venture forth during that time.

Here at Redline Guiding we encourage preparedness — regardless of what the author and owner may or may not have gotten away with back in the 60s and beyond. Meaning we generally carry all of the gear we think we might need if things don’t go as planned. (Less so in the case of our trail runners who accept more risk, rely more on experience, and have learned to adapt, but we’ll get into that soon.) This doesn’t have to mean a literal ton of stuff, just 13 Essentials — modified by the season — along with any specialty items like traction devices for ice travel, or trekking poles, for example. This, we feel, is the default methodology all hikers should employ. Especially new hikers.

The Most Basic, Basics

We don’t mean to suggest a person new to hiking visit their local hiking gear purveyor and ask to be sold everything needed. The person you’re asking may our may not have the knowledge and experience to really help. They may be motivated for the wrong reasons, as well. In any case, we may end up buying too much stuff we don’t even know how to use, let alone under duress or in an emergency situation. There is a fine balance.

So, besides lacking knowledge (and perhaps some common sense), what do the people who are getting into trouble every weekend have in common in terms of missing gear? Besides avoiding wearing jeans and other cotton-made articles of clothing, what should they have? Here are seven heart-of-the-summer basics we suggest:

- Wind/water layer with hood and pockets.

- Insulating layer with hood and pockets.

- Food and water (like a liter).

- Decent footwear.

- Trail *map.

- Headlamp.

- Personal medications (if needed).

This is very basic, the bare minimum. Not even a pack (pockets and tying layers around the waist will do). But without these items you quite simply should not venture into the mountains beyond a half mile or so (a fifteen- to twenty-minute hike, or less if conditions aren’t perfect). Period. We can bring nothing if we want when hiking to short distance, easy-access tourist-centric locales. But beyond that, we should bring those basic items on most hikes, even the seemingly innocuous ones.

NOTE: The absence of a first aid kit and other such safety items isn’t an oversight. It’s nice to have but the reality is it isn’t really needed in a minimalist’s kit. After all, usually it’s too much injury for the kit, anyway (without a first responder’s full kit and knowledge that goes along with it), or you can get by just fine without immediate treatment. A piece of duct tape is a good add, as is maybe an aspirin and some Benedryl).

Beyond Those Basics

To add to that very basic kit, we will want to add these seven other items as we venture higher and further (let’s say a 1000-feet up and/or a mile out, respectively):

- Hat and gloves.

- Sun, bug protection.

- Spare batteries or second headlamp.

- A basic *compass (shows north).

- Extra food and water (add another liter).

- Basic first aid kit.

- Backpack.

Adding these items will extend our range. With these items now in our kit, an attempt on a mountain summit is more feasible and certainly safer. It’s still not a complete kit, not fully. But so far, we still know what everything we’re carrying is and how to use it (even the map and that the red end of the compass needle points north, hopefully). Moreover, we’ve probably cleared ourselves of possible negligence by carrying these simple items. We haven’t even reached the “ten essentials” yet let alone our thirteen items, but the basics are covered.

*NOTE: The map and compass are typically paired and on our “13 Essentials” list they appear as a unit. We separated them here based on their actual, practical value to new hikers. To most, for which the compass really only points to north, a map’s value easily trumps that of the magnetic compass.

Informed Decisions

The mountains are almost always colder than the low-lying valleys and notches where we begin our hikes. This is one of the many things we need to understand and prepare for before setting out safely. Thankfully there are resources aplenty to help us. We begin to understand through learning and experience that to stay warm in the mountains we eat food which fuels our ability to hike which in turn generates heat. When we stop we cool down — quickly and uncomfortably at times. That’s what the layers we carry are for.

The mountains are almost always colder than the low-lying valleys and notches where we begin our hikes. This is one of the many things we need to understand and prepare for before setting out safely. Thankfully there are resources aplenty to help us. We begin to understand through learning and experience that to stay warm in the mountains we eat food which fuels our ability to hike which in turn generates heat. When we stop we cool down — quickly and uncomfortably at times. That’s what the layers we carry are for.

Enough is Too Much

But honestly, what we carry isn’t adequate — or barely so — for a long stop due to a more serious injury or darkness (that’s why the headlamp is on the first list: to help us get out). It gets very cold in the mountains at night, comparatively. Thus, if we really want to be prepared, it goes even further. Not only should we embrace those aforementioned “thirteen essentials,” they better be properly-rated-for-the worst-case-conditions essentials. But now things are getting heavy, especially if we hike in the fall, winter, or spring, during which winter conditions may happen at anytime and should be expected. And forget mountain running, a sport where weight is a serious concern.

Runners Lose Weight

To avoid excessive heaviness we can invest in high-tech, lightweight items, or get rid of them altogether. We can accept the associated risks and choose to make sacrifices. We can adapt. Offering Trail Running adventures and a course now, this has become more of a consideration than ever. It’s a conflict for us, in a way. On one hand we aim to be fully prepared, but the level of mountain running we’re offering simply does not work with the amount of gear necessary to be fully prepared. It’s too much; the sport demands a smaller kit!

Managing, Nonetheless

This is where knowledge, planning, and experience can go a long, long way. Knowing how to avoid a situation, handle one that’s unavoidable, and to adapt when needed, is crucial. It’s similar to the differences between front-country and backcountry medicine where making do is what it’s all about. Using fir boughs as a bed, sticks and leaves in lieu of a proper splint and padding, it’s really seat-of-the-pants doctoring, but knowledge saves the day! When you run you must learn to similarly make do using your wits, what’s around you, and your experience.

As mountain runners we must accept this reality. It’s running. Of which falling is a part. And we’re doing this on trails, in the mountains, in forests. You know it… there are inherent risks!

We’re Not Your Mother

We all very well know there’s a good argument as to why those who venture into the mountains should be fully prepared, but we’re not going to preach. If you want to pack light, whether it’s for running or just because you hate a heavy pack, we suggest you use your head like you’ve never thought possible and really stay in tune with yourself. We also strongly suggest you do this with others, as there is safety in numbers, but we know in the end, it’s your call.

There’s No Assurance in Insurance

![]() Old rock and ice climbers have a saying: “don’t use your ability as protection.” What they mean by this is to wear a harness, use a rope, attach to gear, make anchors, etc. Use protection. Stay protected. That way if their ability fails them, even if just for a second, and they peel off of whatever wall they’re on, they won’t plummet and deck on the ground below. Did you notice we wrote “old rock and ice climbers” at the start of this paragraph? That was intentional. Climbers can be bold or old, usually not both (though Alex Honnold may be rewriting the rules there). After all, is your performance perfect? Every single time?

Old rock and ice climbers have a saying: “don’t use your ability as protection.” What they mean by this is to wear a harness, use a rope, attach to gear, make anchors, etc. Use protection. Stay protected. That way if their ability fails them, even if just for a second, and they peel off of whatever wall they’re on, they won’t plummet and deck on the ground below. Did you notice we wrote “old rock and ice climbers” at the start of this paragraph? That was intentional. Climbers can be bold or old, usually not both (though Alex Honnold may be rewriting the rules there). After all, is your performance perfect? Every single time?

Hike Safe in New Hampshire

Before we end this, we would like to note that in the State of New Hampshire you can buy a HikeSafe Card to afford yourself some protection, all while helping rescue services. The details of this protection are as follows:

A law passed in 2014 authorizes the NH Fish and Game Department to sell a voluntary hike safe card for $25 per person and $35 per family. People who obtain the cards will not be liable to repay rescue costs if they need to be rescued due to negligence on their part, regardless of whether they are hiking, boating, cross country skiing, hunting, or engaging in any other outdoor activity. An individual may still be liable for response expenses, however, if such person is deemed to have recklessly or to have intentionally created a situation requiring an emergency response. — HikeSafe (New Hampshire Fish and Game)

NOTE: The use of bold text to show emphasis is as quoted.

Speaking of rescue services, mountain rescues usually take hours. Many hours considering help needs to first be reached. After all, a simple litter carrying operation will require dozens of people for swapping out carriers, clearing the path, etc. It’s involved. An immobile person may cool too much and die of hypothermia in that time without some form of protection. This is a reality. We really need to consider this when deciding on whether or not to bring that extra layer.

Having a card will not prioritize your rescue. But who knows, maybe it’ll be like having a bumper sticker saying you support the policemen’s ball. Maybe it’ll help, maybe it won’t. We encourage you to get one anyway. Better safe than sorry.