The title of this post is likely going to be taken as a reference to generally bad weather by our readers but, really, its focus is on a specific element of the weather: the wind. On New England’s taller mountains — the ones offering alpine exposure like Mt Katahdin in Maine, Mansfield and Camel’s Hump in Vermont, and Moosilauke, peaks of the Franconia Ridge, and most of the Presidential Range in New Hampshire — often feature high winds in their respective forecasts.

These meteorologists witnessed and measured the fastest wind over land in 1934. Photo courtesy of the MWOBS

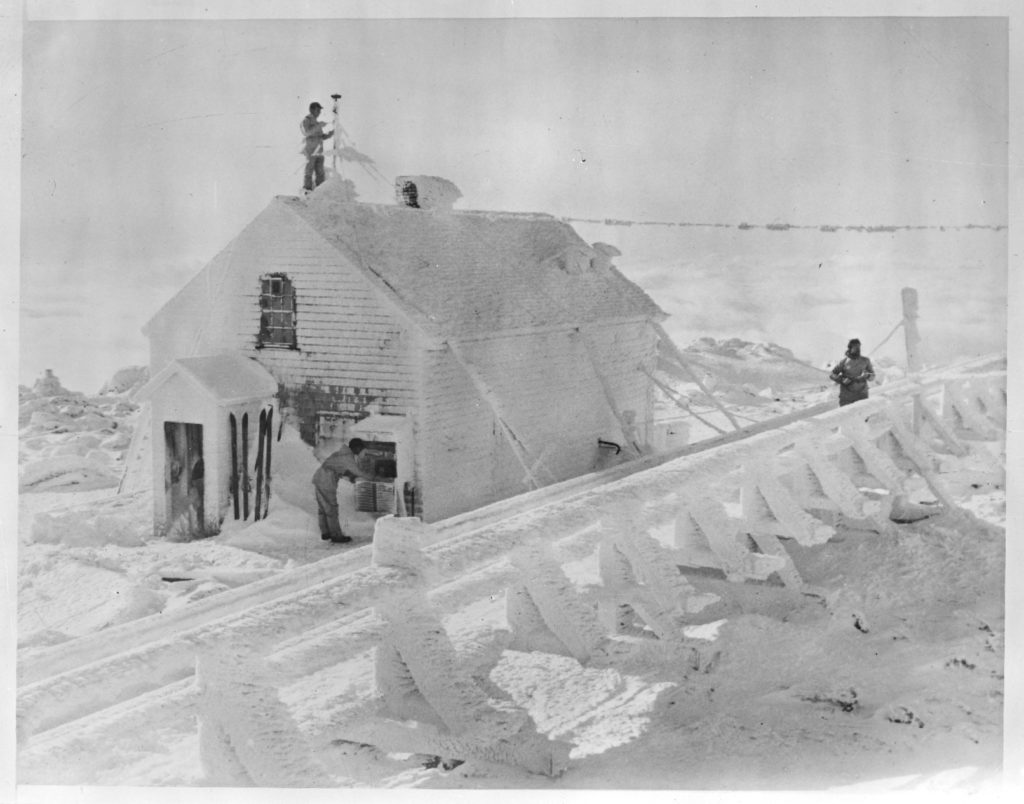

The most notorious of these mountains is New Hampshire’s largest Presidential peak and the tallest mountain in the northeast: Mt Washington (6288ft/1917m). It is there that a human-observed over-land wind speed record took place. On the afternoon of April 12th, 1934, the weather observers (photo above) stationed at the Mt Washington Observatory — which was then a wooden building (photo below) with heavy chains set over the roof — recorded a wind gust of 231 miles-per-hour (372 km/hr). This record still exists to this day, though a slightly higher wind speed has been recorded over the water off the coast of Australia, it wasn’t observed by a human but rather by an unmanned weather buoy.

Mt. Washington Observatory, Jan. 1933. Photo courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

Hiking these exposed mountains often subjects visitors to winds strong enough to get one’s attention. In fact, they can be dangerous if not respected. This is especially true in winter. Not only are the strong winds more frequent, when coupled with already bitter temperatures they create wind chills to die for. Bear in mind, this can happen at any time of the year — remember that wind speed record occurred in mid-April — but winter raises the bar substantially. So how do we stay wind-safe while hiking New England’s mountains?

Staying Ahead of the Wind

Lenticular clouds speak of higher elevation winds. These will sometimes be seen stacked atop one another like a pile of pancakes.

Knowing What to Expect

Obviously knowing the forecast and yielding to it is your most obvious course of action but it doesn’t mean you can’t hike on windy days. In the case of our guided offerings, particularly in winter when the winds are generally stronger and occur more often, we will usually employ a mindset that we will go as far as we can safely go then turn back. How far that is, exactly, will be determined by several factors including the trend: For example, are the winds going to build or diminish over time? Other factors also taken into consideration will include the expectation of occasional gusts versus sustained winds, the wind direction — usually from the west or northwest — temperatures and moisture levels, and the experience level of those up there with us along with their appreciation of such conditions.

Estimating the Wind

Experienced hikers learn that we can put up with a lot of wind — though we find the wind is often over-estimated. When it’s blowing 30-35, for instance, many folks will claim it’s blowing 50 or more. The reason for this is we’re just not used to winds of this magnitude. But when you’re up there being buffeted by the winds, it’s easy to think it’s more than the reality. Over time we become more experienced, we learn, and our estimates tend to become more accurate.

Be Wary in the Windy Woods

One way to get out there and hike when the winds are cranking is to simply change up the plan opting for a mountain with less exposure. That said, if in the woods, falling branches, “window-makers,” deadfalls and blowdowns make things pretty dangerous so one has stay very alert. In such conditions wearing a climber’s helmet can be an important kit add-on. Sticking to trails sheltered by the mountain can help reduce some of these dangers, however. If, for instance, strong gusts or sustained winds are coming out of the west, hiking on the east side of a mountain can effect a dramatic change for the good.

Standing Up to the Wind

If hoping to actually experience some of these alpine winds, using trekking poles can be incredibly beneficial. Even placing your feet purposely can help you maintain balance and stability. It can be tough, however, if the winds are gusty due to wind speeds being variable — the wind stopping suddenly can also have an adverse effect — but hikers need to expect this to occur and be ready for it by having a pole planted on the windward and leeward sides. This will prevent being blown over during a gust as well as falling over when the gust stops.

Going With the Wind — and Returning

Hiking with the wind to your back can be a game changer, but if you will be reversing your direction such as hiking out and back by the same trail, you need to turn around often to sample those pushing winds since you will be heading into them on the way back and have no choice but to endure them. We need to know that we can deal with this. Another factor to consider on a hiking trip in high winds is to imagine the consequence of a fall. If long, sliding falls are likely or if hiking on rocky, icy terrain when a fall is likely to result in injury or the breakage of gear, perhaps changing things up such as the mountain or the objective of the day is the smartest move.

This photo of the Eastern Snow Fields on Mt Washington shows cloud and spindrift, indicative of high surface winds.

Respecting the Winds

There’s nothing wrong with being blown away, but only if that means remaining in awe while avoiding the literal usage of the term.