She was taking a full day navigation course with us in preparation for a solo thru-hike of the 100-Mile Wilderness in Maine. In that class, even though it is not an orienteering course, per se, we do discuss what to do if you find yourself lost on a hike. We always suggest looking behind you for starters. People are turned and misdirected by water bars and other drainages all the time. That said, often the answer is mere feet or yards behind you. If that’s not the case, we always suggest not panicking and instead going through the motions of taking off your pack, calmly sitting down, and poring over your map. You do carry a map and keep it handy, right?!

She was taking a full day navigation course with us in preparation for a solo thru-hike of the 100-Mile Wilderness in Maine. In that class, even though it is not an orienteering course, per se, we do discuss what to do if you find yourself lost on a hike. We always suggest looking behind you for starters. People are turned and misdirected by water bars and other drainages all the time. That said, often the answer is mere feet or yards behind you. If that’s not the case, we always suggest not panicking and instead going through the motions of taking off your pack, calmly sitting down, and poring over your map. You do carry a map and keep it handy, right?!

Our student, as luck would have it, did get off trail in her travels and sure as can be, felt panic rising. Tears welled up in her eyes and she fought the urge to pick a direction and run — the odds are 1:360 it’d be the right one so it’s an unwise option. Then, as if by some miracle, she heard Redline Guide Mike Cherim‘s voice in her head. He taught her the course and it was his voice she heard calmly telling her what to do. Sit down, have a snack, take out your map, and figure it out, the voice spoke to her. She did and was soon able to figure out where she went wrong.

Sage (Common Sense) Advice from Long Ago

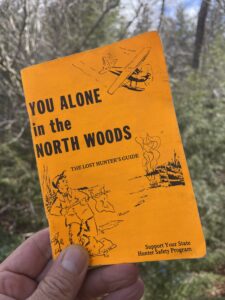

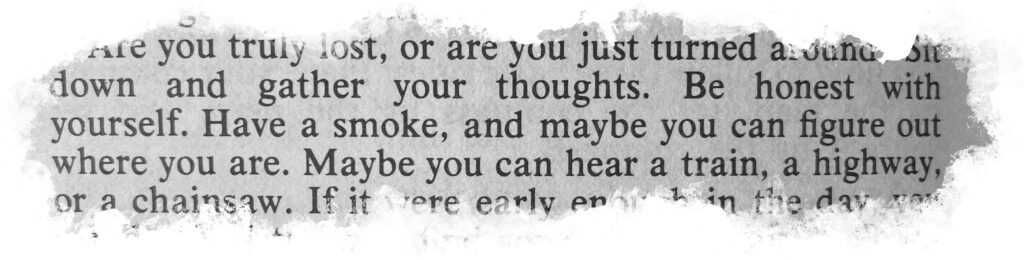

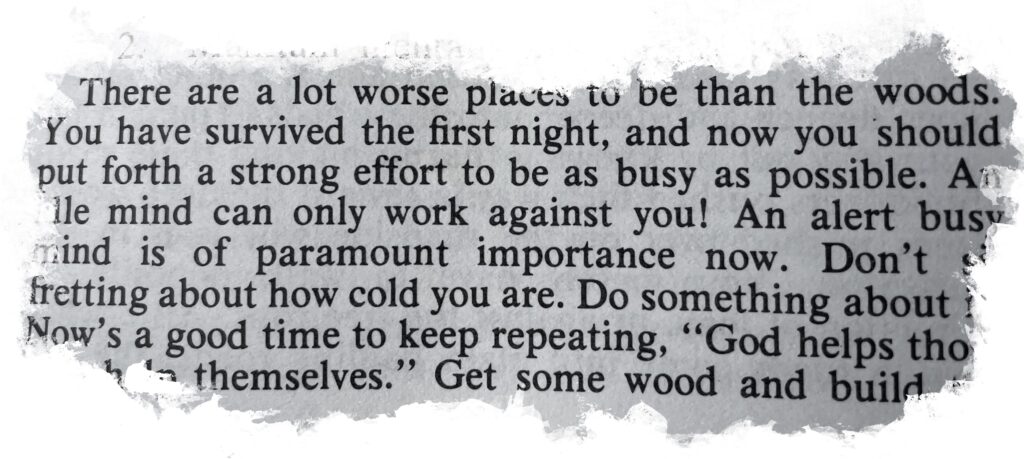

Mike’s advice isn’t new or novel. He got it from a very old pamphlet published by the State of Maine, Department of Inland Fisheries and Game, titled: You Alone in the North Woods. It’s a legendary tome for those in the know, that began its life as Volume 1 in 1972 — a wealth of knowledge in a mere (then) sixty pages complete with hand-drawn illustrations. Mike has the third edition from 1974. On one hand it’s a collector’s item, but it still offers such sage advice such as to sit down, have a SMOKE, take out your map, and figure it out. That said, the 11th edition from 2020 has probably substituted that particular nugget of wisdom. But who knows… it’s Maine (and we mean that in the most loving way possible).

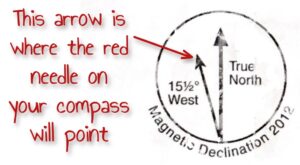

So far this advice doesn’t call for raising the alarm. Being misplaced isn’t a reason to panic and it’s probably not going to kill you, nor will spending the night if you carry the right stuff and/or know what to do with what you have. If, of course, you’re dealing with an injury or illness, by all means, please jump to the section that covers calling or texting 9-1-1. That is an appropriate action. But if you’re just unsure where you are — and you can’t follow your way back to salvation, the gig’s not up yet. Have that smoke, if that’s what it takes, and go over that map. Use your compass. Use your head. Find magnetic north. Note that magnetic north on your map is going to be roughly 15 degrees — the current “declination” value in NH — to the west of true north. Depending on the map, you may have a symbol that clearly shows this (see inset).

So far this advice doesn’t call for raising the alarm. Being misplaced isn’t a reason to panic and it’s probably not going to kill you, nor will spending the night if you carry the right stuff and/or know what to do with what you have. If, of course, you’re dealing with an injury or illness, by all means, please jump to the section that covers calling or texting 9-1-1. That is an appropriate action. But if you’re just unsure where you are — and you can’t follow your way back to salvation, the gig’s not up yet. Have that smoke, if that’s what it takes, and go over that map. Use your compass. Use your head. Find magnetic north. Note that magnetic north on your map is going to be roughly 15 degrees — the current “declination” value in NH — to the west of true north. Depending on the map, you may have a symbol that clearly shows this (see inset).

Yes, Map and Compass is a Thing

This isn’t an article about how to use a map and compass. It could be, an extremely detailed one at that, but that would turn ’em away in droves. Even though many sadly don’t realize they could use that simple tool for something as mundane as venturing off into the woods to make a private poo. But we digress. If you want to learn map and compass, you know where to find it. It’s out there.

Yes, And There are Gizmos

In this article we aren’t going to get into detail about the merits and downfalls of electronics and their reliance on batteries. Or using your phone for something besides a phone… and maybe a camera. Or the devices that talk to satellites saying things like “Help Me, I’m Here” at the punch of a button. Honestly, barring injury or illness (to include hypothermia) to which an appropriate backcountry medical response is called for, these items aren’t usually needed. But for that statement to be true, the following must apply.

- You carry an up-to-date topographical hiking map, folded to the location of the hike, and you study it beforehand and during the hike.

- You check the map at every junction until familiar with the area. If you’re hiking with others, take on junctions and water crossings as a group.

- Pay attention. Even if you’re not leading the hike, try to stay engaged. Read the trail signs, note the distances, the time, and the elevations, if so equipped.

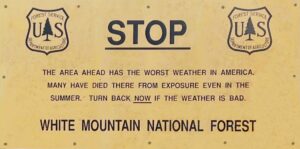

- Use your head as well as your resources, check the weather and don’t do it if it’ll be bad — especially in the alpine. The mountain will be there another day.

Other Navigation Aids

The way below treeline is mostly marked with 2″x6″ paint blazes. White for the A.T., blue for trails that connect to the A.T., and yellow for all the others. This may vary as one gets further and further from the A.T., and within Wilderness areas, blazing isn’t allowed.

Above treeline, if you carefully picked the day and visibility dropped anyway thanks to that crazy mountain weather, carefully navigate from cairn to cairn (pile of rocks). Even using paracord to stay connected to one cairn or person next to a cairn while looking for the next one. They should be roughly 50′ apart. One can also try to focus on the boot pack or treadway between scree walls, at least in places. And if that fails, if you have a map and know the terrain, “handrailing” with terrain features is sometimes another option.

Seeking Outside Help

If you have battery life it may be tempting to post on Facebook or some other social media platform looking for some crowd sourced advice and wisdom. And is that a bad thing? Well, if it’s not a full-on emergency, and hasn’t escalated to one yet, one might think asking a large hiking group is a solid idea — instead of calling 9-1-1. The concern probably being that calling for help will automatically trigger some big call out or that the National Guard is notified along with your next of kin. It won’t. The help you receive will be an appropriate level.

Do Call 9-1-1

We would have to disagree with the idea of posting to social media. While it could possibly lead to a good outcome, it’s akin to blowing up an ant hill with dynamite. Calling emergency services through proper channels, even if not fully in need of said services yet, would provide a link to a knowledgeable person to talk to. Not the 9-1-1 operator, exactly, but the Fish and Game officer (in New Hampshire) they would connect you to would have the resources and know-how to help you become reoriented. And if the advice proved unworthy to resolve the situation, with “location services” turned on on your phone, emergency personnel would know your approximate position.

We would have to disagree with the idea of posting to social media. While it could possibly lead to a good outcome, it’s akin to blowing up an ant hill with dynamite. Calling emergency services through proper channels, even if not fully in need of said services yet, would provide a link to a knowledgeable person to talk to. Not the 9-1-1 operator, exactly, but the Fish and Game officer (in New Hampshire) they would connect you to would have the resources and know-how to help you become reoriented. And if the advice proved unworthy to resolve the situation, with “location services” turned on on your phone, emergency personnel would know your approximate position.

But What if There’s No Service?

Cell reception can be spotty in the wild spaces in our state, or any state for that matter. So if you grab your phone, ready to ask for help, and you find you have no bars, no service, try calling anyway. “No service” means you cannot reach a cell tower, but it doesn’t mean you can’t reach another tower. Most other towers out there have 9-1-1 repeaters so dial that phone, then wait as an indirect connection is hopefully made. And if a call simply doesn’t go through, do try sending a text instead. If your battery is low, maybe even try that first. They may be able to call you… if your line is open.

Cell reception can be spotty in the wild spaces in our state, or any state for that matter. So if you grab your phone, ready to ask for help, and you find you have no bars, no service, try calling anyway. “No service” means you cannot reach a cell tower, but it doesn’t mean you can’t reach another tower. Most other towers out there have 9-1-1 repeaters so dial that phone, then wait as an indirect connection is hopefully made. And if a call simply doesn’t go through, do try sending a text instead. If your battery is low, maybe even try that first. They may be able to call you… if your line is open.

Getting the Word Out

While it may sound old fashioned, there are other ways to get found that don’t rely on connectivity to the Internet or some constellation of satellites. If it’s seen, the smoke from a smoky fire, for example, can signal both duress and your location. A whistle or other noisemaker can do the same. Carry one to be prepared. It’s likely the buckle on the sternum strap of your backpack features an in-built whistle. A reflective device like a CD or some other mirrored surface can also be used as a signaling aid. A brightly colored tarp as a flag may also serve. Use your imagination.

These are all effective during the day, but at night it gets harder. That said, a glow stick tied to the end of some paracord and spun over your head makes for a highly visible ‘O’ and there are other night aids such as flares, but this is beyond what most hikers carry.

What Else is Out There

One other important thing worth doing is to be proactive in your notifications by telling others your plan beforehand, giving them a reasonable timeline, then just sticking to it. That way if you don’t check in as expected, at least your contacts can notify authorities on your behalf. It’s nowhere near as good as you calling 9-1-1 yourself, but the whole situation is less than ideal. If it were ideal, you’d be in here, not out there.

Alternatively, if you don’t have a life-line at home, leaving your itinerary on the car is suggested by some but others will argue it may pose a security risk. You might want to think this one over.

And at the End of the Day…

Don’t get lost. Plan ahead and prepare — like the first principle of LNT states. Have the right tools and know how to use them. And last but not least, stay out of trouble by holding back, really picking your days. Be reserved. We’d offer you our well wishes and the best of luck, but you can do better than that… ah, okay, what the heck. It can’t hurt. Good luck out there!

![]()