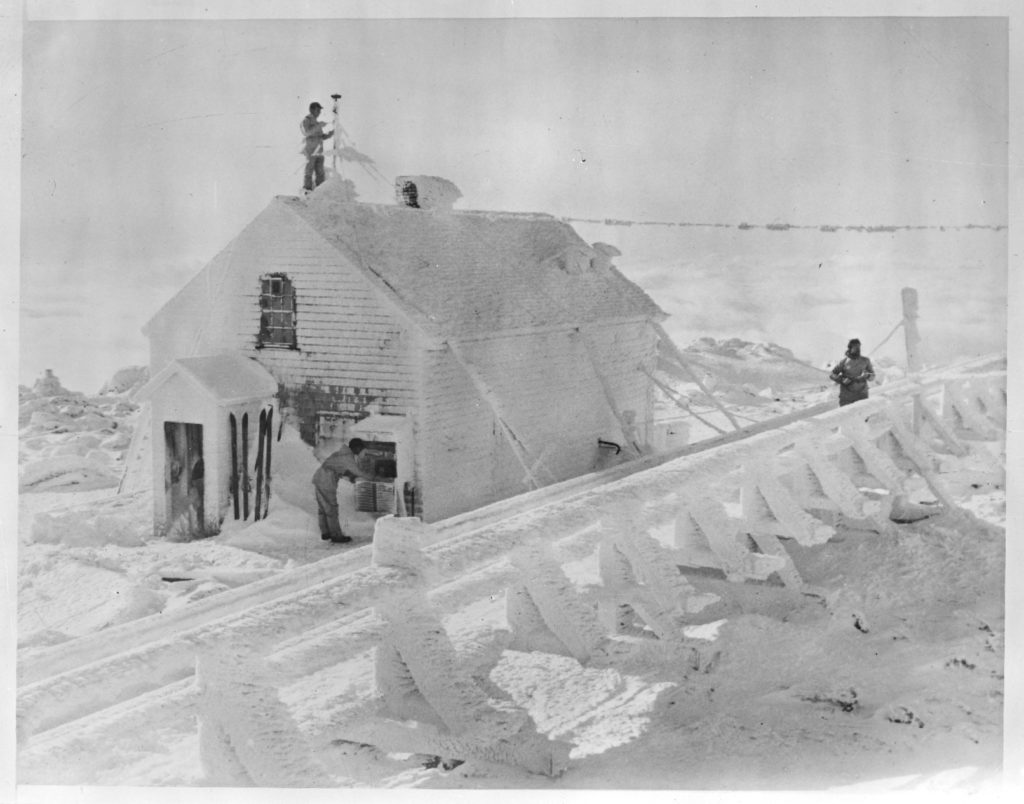

Mt. Washington Observatory, Jan. 1933. Photo courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

While writing an article yet to be published on another website (now published), the topic of Mt Washington’s weather crept in — fast and unannounced like the weather up there on the exposed 6288 foot (1917 m) summit itself. In an effort to be concise, we initially wrote something along the lines of this:

Three major weather systems converge over its peak and being that it’s the seventeenth highest mountain and most prominent topographical feature east of the Mississippi River, the combined effect of these systems, multiplied by the terrain on this mountain, can create some memorable weather events at any time of year, although particularly in winter.

We were thinking, what with our limited weather knowledge, that we were referring to the mid-latitude Jet Stream, the Alberta/Canadian Clipper, and, well, what we knew only as a coastal flow from the Gulf of Mexico. And that was what we had always heard through various sources, but before committing to this statement, however, we did some research.

What we learned wasn’t too far removed from what we believed, but the answer was so much more involved than we ever realized, which is the main reason for this break-out, stand-alone weather article.

We learned we aren’t the first to mistakenly state that Mt Washington is at the convergence of three common storms or systems. We also learned that it is not entirely correct as it is the storms’ tracks that affect us more than the type of low pressure area. And we are by no means limited to just three, either. So the quote should be that Mount Washington lies in the path of three common storm tracks, for example:

- East Coast:

- These include Coastal Runners, Inland Runners, lows from the OBX, lows from the Delmarva Peninsula, Nor’easters, hurricanes/tropical storms/tropical depressions, or decaying variations such as Miller Type As or Miller Type Bs.

- Southwest:

- These track up the Ohio River Valley and include Great Lakes Cutters, Appalachian Runners, Apps Runners, Panhandle Hooks, Panhandle Lows, Texas Hookers, Gulf Lows, Salient Lows, or Colorado Lows.

- West/Northwest:

- These come from the Great Lakes and along the St Lawrence River Valley and include Alberta Clippers, Manitoba Maulers, or Saskatchewan Screamers. And then upper level low/trough passage typically brings lake-effect snows which can spread all the way over to White Mountain National Forest.

Learning this muddied up the waters, so to speak, while at the same time offering clarity. This led to us questioning the other things we thought we knew about the weather on this notorious mountain. It was time to dig up some weather history and a few facts worth sharing. Since it’s fairly well known — for the past 91 years — that a wind speed world record took place on the summit, we figured the topic of Mt Washington’s ridiculous winds was a good place to start.

A Menu of Wicked Weather

If one wishes to become acquainted with some of the most revered and respected forces of nature, Mount Washington is the place to be. It offers a lot of bang for the buck, so to speak. Let’s check out its foul weather smörgåsbord.

Mount Washington’s Wind

As mentioned, the observed wind (surface) speed world record was measured atop the summit. This took place on April 12, 1934 — 91 years ago. The speed, recorded by a heated anenometer which was later verified by the then National Weather Bureau, clocked in at a shocking 231 miles-per-hour (371.75 kph)! One would think it must have been a truly terrifying experience for the observers, wondering if the building they sheltered in — what is now the Stage Coach office — would stand its ground or be blown off the mountain despite being held down by chains and reportedly built to withstand 300 mile per hour (482.8 kph) winds. But true to science, they focused on the event with purpose. You can read more about this history on the Mt Washington Observatory website.

This is the observed wind speed record and remains so. A new wind (surface) speed record of 253 miles-per-hour (407.16 kph), however, was recorded by an unmanned weather station on Barrow Island off the coast of Australia on April 10, 1996 breaking Mt Washington’s surface wind speed record by an added “fresh breeze” of 22 miles-per-hour (35.40 kph). These extreme winds are difficult to even comprehend. And fortunately quite rare. Nothing beats Mt Washington for consistency, however, since on average, hurricane force winds will scour the summit 110 days each year!

Tuckerman Ravine fills with snow. Photo by Ryan.

Mount Washington’s Precipitation (Snow)

The average amount precipitation on the mountain each year is atypical at almost 97 inches (246 cm). The vast majority of this precipitation falls as snow. And if you think that all that precip makes for a lot of the stuff, way back in 2019, when this was written, the summit received over 300 inches (762 cm). Wow!

Coupled with the prevailing west winds blowing over and around the summit scouring the Labrador-like tundra on the Presidential Range, an enormous amount of snow is carried from the west side of the mountain to the east side filling the major ravines on that side, notably Tuckerman and Huntington Ravines along with Raymond Cataract. This snow has measured a staggering 40-50 feet (12-15 m) deep in Tuckerman Ravine above “Lunch Rocks” according to the Mt Washington Avalanche Center (MWAC)‘s “Snow Rangers.” No wonder snow often remains in there into the month of July luring even then some diehard skiers unconvinced the season has ended. Then, of course, their “vert” is only tens of feet skied on a narrow, dirty strip of snow.

In the winter and even well into the spring, this blown snow is packed into what’s known as wind slab. This concrete-like snow layer can fracture and avalanche and regularly does, endangering backcountry skiers and others. We are fortunate to have the avalanche-predicting MWAC also located on this mountain. Their insights are invaluable undoubtedly saving many lives.

The snowy precipitation can be a bit on the heavy side at times. During a 24 hour period in February of 1969, the snowpack grew by a record-setting four feet (1.22 m). That’s a lot of snow in a very short amount of time! While other months of the year have never yielded such volume, precipitation in the form of snow has fallen onto the summit in some measurable quantity in every month of the year. It may be a hot August day in the Mount Washington Valley, but on the summit it can feel like winter, complete with all of the dangerous side effects we know and respect. It’s one reason, coupled with its deceiving size and ready access to a huge populace, why this mountain has proven to be so dangerous to so many.

Mount Washington’s Temperatures

If the wind and snow isn’t enough to show just how crazy it gets up there, maybe some discussion about the mountain’s temperatures will seal the deal. In the text above we have used terms like “alpine” and “Labrador-like tundra” quite literally and not just to be dramatic. The low temperatures on Mt Washington have been often recorded and compared to the coldest places on earth: the poles, the summit of Mt Everest, etc. These comparisons were likewise undramatically literal. Case in point, on January 16, 2004, an ambient temperature of −43.6°F (-42°C) was recorded along with sustained winds of just over 87 miles per hour (140.01 kph). This resulted in a wind chill value of −102.59°F (-74.7°C). Preceding and during the event — which lasted 71 hours, the wind chill never rose above -50°F (-45.56°C). These numbers aren’t too terribly shocking to us as guides up there, however. We often see -20°F (-29°C) days. Because of this, on some days we just don’t venture any further than treeline, and not without risk even then.

Those are the lows. The highs aren’t nearly as impressive. The highest it has ever been on the summit is only 71°F (21.67°C) which was measured two times, once on August 2, 1975, then more recently on June 26, 2003. It never really warms up up there and only exceeds the 60°F (15.56°C) mark a mere 16 days per year.

Mount Washington’s Cloud Shroud

Our article wouldn’t be complete without mentioning the clouds. What with all that precipitation, a lot of clouds are to be expected. To put that statement in perspective, realize that the skies are clear from sunrise to sunset — not shrouded in clouds — an average of only *fifty days each year. (*Please note that while this last fact has always been “known” to us, we were not able to verify this information.) Often layered above the mountain are lenticular clouds which are indicative of the high winds up there. Sometimes clouds are seen literally pouring into the ravines on the east side like a liquid. Other times the clouds completely isolate the upper reaches of the mountain, cutting it off from the rest of the world. The clouds up there add danger and intrigue, often both at the same time.

A History of Notoriety

For as long as human eyes have set upon this mountain, its power and penchant for killer weather has been well known.

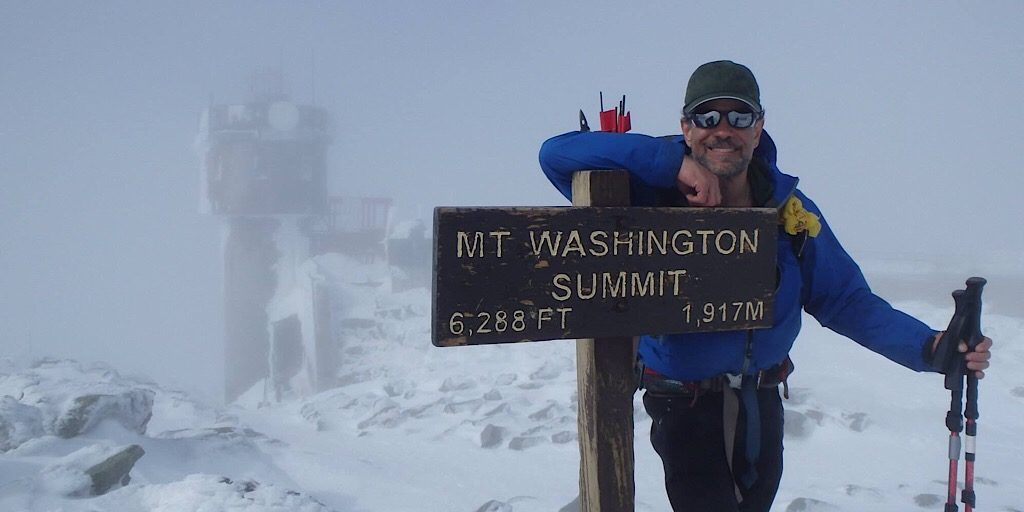

Not what it seems. A hiker comfortably rests up after summiting the mountain in the depths of winter. Photo by Ryan.

According to Wikipedia, indigenous peoples living here before European settlers arrived referred to the mountain as Kodaak Wadjo meaning “the top is so hidden” or “summit of the highest mountain.” Other tribes named it Agiocochook meaning “the place of the Great Spirit” or “the place of the Concealed One.” The Algonquians, which are well known to this region, called it Waumbik meaning “white rocks.” If it’s not clear, many of these names are weather-related. Mount Washington is a small mountain on a scale of all mountains, but stands on its own with its demonstrations of nature’s fury. As has been oft repeated, our little New Hampshire mountain is “Home of the World’s Worst Weather.”

Cloudy but calm and comfortable, the author enjoys a peaceful Mount Washington summit.