If you’re injured in the backcountry there are possible many scenarios with many outcomes, but most have one thing in common: Rescue will take longer than one may expect. To give a clearer understanding of why, this fictional tale describes a typical rescue from start to finish.

Chapter 1: The Situation

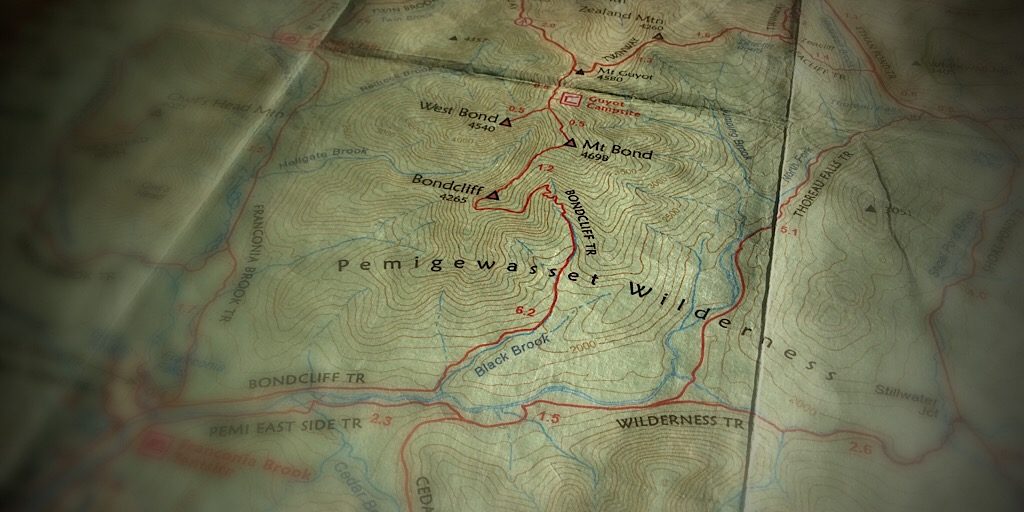

To begin our story, let’s consider this: It is early June and you’re hiking a Bonds traverse the shortest way possible with a friend. You get on trail bright and early at 7:00 AM on the northern end at the Zealand trailhead. Your plan is to bag Zealand, West Bond, Bond, then Boncliff. You hope to finish your forty-eight there, stopping long enough for that classic Bondcliff photo, weather permitting. Your friend has already finished their list; you’re both very experienced hikers.

It’s good that you’re not alone, even though the ideal party size is four (a patient, a caregiver, and two runners). It should be noted that both of you are carrying a decent amount of gear. You with the “ten essentials,” and your friend is carrying the thirteen essentials, preferring the thoroughness of that list. Both of you have your cell phones, but neither of you is carrying a PLB or personal locator beacon — though those things really provide mixed results. The weather is average for June, in the 50s up high, but it’s supposed to be sunny for the entire day albeit very windy. The Mt Washington forecast is calling for gusts in the 90s out of the northwest. Knowing this, you hypothicize that the winds on the summits, excepting that of Zealand, and the col between Bond and Bondcliff are going to be likewise ripping something wicked. You will be correct as you will see first hand in a few hours. To help you stay on your feet, you’re both bringing trekking poles.

Skipping Ahead

Let’s fast forward a bit speeding up the day. You made it to the AMC’s Zealand Hut, stopped for a fresh cookie and to fill your water bottles, then you took on the most significant ascent of the day climbing up to Zeacliff. You stopped there for a while grabbing some awesome photos of Whitewall Mountain, the stunning Zealand Notch view, and a selfie with you and your friend. It was a great day so far — both of you were feelin’ it.

After Zeacliff you continued on the Twinway, stopped at the Zealand summit for a photo of that well-known sign. There you held up a sheet of paper that said “45” and took a photo (congratulations, by the way). The photo caption will read “three more to go” when you post it on Facebook in a few weeks. You and your friend continued on over the true summit of Mt Guyot and onto the junction with the Bondcliff Trail. After pausing to take it all in you continued on over the Guyot south sub-summit then dropped down toward the junction of the Guyot Tentsite spur. You both wisely took a water inventory but realized you each had more than enough to get you to the next crossing allowing you to forego the significant drop down to the Guyot spring. You moved on; the West Bond Spur junction was close at hand.

Upon arriving at the junction you both considered dropping your packs for the one-mile detour to the summit and back. You were ready to do it but your partner spoke up declaring the notion a bad idea asking “what if one of us gets hurt?” This called to your better judgement so upon further reflection you agreed. As it turned out nobody got hurt on West Bond, and the packs didn’t even come off your backs, but you didn’t know that going in. Smart. Just imagine if someone did get hurt and the packs were left behind. Awkward!

After you experienced the winds on Guyot’s summits and on West Bond, you were both comfortable going on feeling that what lie ahead would be manageable. And you did manage — for a while. The winds on Mt Bond, being the highest point on that ridge, were indeed ripping something wicked. Even more so in the col between Bond and Bondcliff. There, thanks to the Bernoulli Effect which compressed the already strong winds as it would a fluid as they passed through the narrow dip in the ridge, you were really being buffeted. You both made it through, though. With the help of those poles. That was a good choice!

It was a glorious day. The temperatures ended up being ten degrees warmer than that which was forecast making it feel downright balmy. You both wore an upper body wind layer to take the bite out of the wind. On the bottom you had “zip-offs” with the lower legs zipped off. Sunglasses and sunscreen were both in use. The sheets of paper that had “46,” “47,” and “48” written on them stayed in your pack. That was what you were thinking about as you pressed hard against your poles pushing upward, racing the final paces to the Bondcliff summit with a huge grin on your face. That’s when it happened.

It was really bad timing on the part of the wind. It was an atypical gust — the Mighty King of Gusts — and it slammed you down, hard. It happened just as your leg was tight between two rocks. The upper part of your lower left leg carried its momentum forward, but the lower part held fast between the rocks. The twin snap felt audible above the wind and probably was. By the angulation — not being a doctor or anything — it looked like your lower left leg was completely broken. You were in some pain, that was for sure. You screamed. That could heard above the wind. And that brings us to now.

Chapter 2: The Present

There’s nobody on the summit at this time. You two made pretty good time despite your extended Zeacliff stop, and you passed several others headed this way. The strong, erratic winds, however, were probably sending some packing while others were certainly being delayed. Not one person was visible from behind. And nobody knows if anyone was coming up from Lincoln Woods. It looks like you’re on your own. At least for now.

What To Do First

As was noted, your friend is a pretty experienced hiker, as are you. Luckily you have both taken a Wilderness First Aid course so you kind of know what to do. While gritting through the pain you both layer up. The pain, wow, this was never fully described in the classroom. You put your puffies on and replace your pant legs. You leave your left one off, of course. Your friend, the one carrying the 13 essentials, has a foam sleeping pad and is carefully handing to you in the wind. It’s not easy, but you’re able to get it under yourself. It is important to get off the ground and get sheltered up at this point and you know this.

After these initial steps your friend pulls traction on your lower leg straightening it. This hurts like hell, but you try to maintain your control and instead endure the pain the best you can. Once straightened, being it’s a lower leg, your friend releases the pressure and works calmly on creating a big, ugly, fat, and fluffy splint (this is how they’re described in the backcountry) to hold the leg in-line and protect it from further injury. If only this stopped the relentless pain.

You both have additional layers, extra food and water, and the situation is being managed pretty well, all things considered. Now it’s time to improve the sheltering situation using a tarp, a bivvy, or whatever is at hand. This would include sitting on a pack or on fir boughs to get off the ground if your friend hadn’t brought that pad. Your friend also had a tarp so that goes over you. Awesome. You’re pretty comfortable, albeit still in a lot of pain, and no longer in immediate danger of succumbing to hypothermia. Yes, even on a nice day in June.

Seeking Help

If others were there, these steps could be carried out while the first aid and whatnot was going on. But they weren’t so we’re going in a logical, necessity-driven order. Now it’s time to get help. You know you’re not walking out. You can’t even stand up. Between wind and your injury, you can’t even really make it to the shelter of the woods. You’re stuck on the summit of Bondcliff! But already we can see how things could be much worse. We’re relieved for you.

You friend pulls out a *cellphone. The carrier on that phone is AT&T but there is no cell signal. Your phone, with Verizon, is likewise useless. Under your tarp your face lights up as you remember something from your WFA class, though. The instructor, as you recall, said: Try dialing 9-1-1 anyway. You might not have cell service, but you might be able to reach a 9-1-1 repeater and reach an operator.” Excitedly you remind your friend of this little known fact then you both try it pressing the buttons on your phones. (*See communications notes.)

Unfortunately it didn’t work, the *nearest repeater must be neither out of sight or too far away. It looks like your friend will have to go get help while you stay put. Your friend leaves you few more clothing items and a bit more food and water, looks grimly at you, then wishes you luck while you wish them the same. You know it’s going to take a few hours just to get to the Lincoln Woods parking area and the US Forest Service Ranger posted there. You close your eyes and begin the wait. Your friend starts hiking. (*See communications notes.)

Chapter 3: The Conclusion

The distance to the Zealand Hut is shorter, but it’s a lot more difficult and potentially dangerous so heading down towards Lincoln Woods makes sense even though it is nearly nine miles away. Your friend isn’t a runner but hurries as much as possible making it to civilization in only three-and-a-half hours. Thankfully there is indeed a ranger there so help is at hand more quickly. Otherwise your friend might have had to drive all the way to Lincoln before making a call to 9-1-1. Reaching the Ranger first may have saved a little time.

Wheels in Motion

The USFS Ranger is alarmed as she listens, then she gets on the radio and calls in the situation to her district office. Her supervisor asks to speak with your friend while simultaneously patching the call through to the Fish and Game. It is the F&G that will coordinate the rescue at this point.

The Fish and Game commander gets on the phone and the pertinent information is collected and recorded: who, what, when, where, and how. Then “how” comes up again as the supervisor considers the options on how he is going to rescue you. There aren’t many viable options. The powerful winds are supposed to continue right on through the next two days as a slow-moving front sweeps the area and the commander, with his decades of experince, knows that an airlift medivac isn’t on the table. The only thing they have left is the use of their personnel, their “four-wheeler” OHRVs, and volunteer manpower.

He gets off the phone with your friend, the ranger, and the district office, and makes another call. First to mobilize some Fish and Game officers, sending them as a sort of advance team. After mobilizing the team the commander gets on the phone again calling out to the PVSART (Pemigewasset Valley Search And Rescue Team) dispatcher letting them know what’s going on. There’s not going to be a “callout” until the advance team further assesses the situation but he figures the heads up will be appreciated.

On Bondcliff

Two Fish and Game officers are shuttled down Lincoln Woods Trail on two large four-wheelers. They stop at the bridge over Franconia Brook and continue on foot. The two are super fit and despite large overnight-ready rescue packs make great time covering the distance to Bondcliff, doing so in just a hair over two hours, stopping only long enough to get situation updates from hikers coming from the direction of the scene. They arrive close to sunset and quickly spot you. You’re still wrapped in your tarp and you have two hikers that have stayed with you while help was on the way.

You’re in a ton of pain but still okay thanks to a combination of your preparedness, having good layers, your foreword thinking, and the kindness of others to help keep your mind occupied during these long hours. You did have to pee at one point, and that was difficult and extremely painful, but you’re here, and now the Fish and Game is also here. They speak with you, find you totally aware and oriented. This situation is not life threatening. The officers tell you their plan and you accept it — you have no choice. The pain is so intense you just want it to end now.

One of the officers steps away to communicate with the scene commander via *satellite phone and relays the situation. He says the patient — hey, that’s you — will need to be littered out by hand using volunteers since nature won’t cooperate; it’s way too windy for a helo. Being that you’re generally okay the officers decide to make you as comfortable as possible for the night and bivouac with you on Bondcliff overnight. The sunset is beautiful but after that the darkness comes and the three of you — the two good samaritans left after the officers arrived — have a long, not-particularly-comfortable night on the mountain. Eventually a beautiful sunrise will warm your soul and amaze you, but the wait involves many, many less-than-pleasant hours, for all parties. (*See communications notes.)

The Calvary

Back at Lincoln Woods the scene commander relays the situation to the other officers standing by as well as to PVSART, whom he has on the phone. The plan is to have the F&G advance team overnight with you while he coordinates a carry-out using Fish and Game officers and PVSART personnel in the morning. It will be decided after the initial PVSART callout response if other organizations like AVSAR (Androscoggin Valley Search And Rescue) will need to be called. The scene commander releases his personnel telling them to be back by 7:00 AM the following morning ready to hike.

Meanwhile a PVSART volunteer gets the ball rolling writing down “Callout #28” on a sheet of paper bearing many names and numbers. The phones start ringing. Within an hour thirty-two PVSART personnel have stepped up giving up their Sunday for you. You should feel honored. By the way, talk of your accident, and your preparedness, has already spread on social media and the response is positive. Thought you might like to know you’re not being vilified.

Between the PVSART people and a half dozen F&G personnel there’s no need to involve other agencies and by 7:30 AM there are already people being shuttled to Franconia Brook by way of the four-wheelers. All eyes are on them as they pass other hikers out for the day in hopes of hiking the Bonds or Owl’s Head. Some know what’s going on from Facebook while others just know it’s a rescue or recovery — they pray it’s not something too bad. They empathize with the unseen patient, assuming it’s a hiker like them. Wow, they marvel at the sheer number of people wearing lime green shirts, all the volunteers that are involved. It’s an impressive show. These folks are really dedicated!

End Game

Eventually, as you know, everyone makes it up to you. They bring you a nice carbon fiber litter to carry you in, then begin the process of “packaging” you. You might want to pee before they get started, by the way. They are happy you said something now and you take care of business, difficult and painful as that may be.

It doesn’t take long before they get you moving down the mountain and to the “Stairway to Heaven.” There they struggle. This part involves the use of rope to help secure your litter as they lower it over this rock staircase of sorts. More pain. The good news is that the winds are a bit diminished now that you’re in the shelter of trees.

Once past that natural obstacle the carryout is pretty straightforward. Not easy, but no real surprises aside from one stream crossing, and the team makes that look easy. It takes several hours but they eventually get you to the bridge crossing Franconia Brook and litter you across. On the other side a four-wheeler awaits. The volunteers are dirty and tired and very happy to see the machine as they continue out on foot. You’ll be glad to know they’ll be home by dinner. I can tell by the look on your face that youre psyched about being done with this whole thing, too. It’s a bumpy ride and it hurts, but it’s fast, and soon they transfer you to a gurney and slide it into the back of a waiting ambulance. You, my friend, have been rescued.

The scene commander sticks around until all of the PVSART volunteers check back in and his people and equipment return safely. He goes back to his office to begin the paperwork and to prepare an official statement to the press. I’ve already heard that because of your Hike Safe card and your preparedness, this one’s on them. Great news, right?

Oh, by the way, regarding the 48… sorry, but you’ll have to come back for this one. Being carried doesn’t count.

*Communications Notes: This is a fictional piece of writing of which some parts are contrived for the sake of telling this possible outcome. According to a F&G spokesperson the actual communications capabilities on Bondcliff are as follows: Currently 9-1-1 repeaters may be available to some cell phone users, while those with Verizon will likely have actual cell service. Satellite phones are no longer necessary in that area. It should also be noted that the two did not have a PLB or Spot device as mentioned in the story, but these things are not the end-all, be-all answer and have proven unreliable in the past. If using one for yourself, which isn’t a bad idea, you do need to know how to use it and understand its limitations. Lastly, do be aware that while this story is contrived, it does quite accurately describe lots of places in the White Mountain National Forest, and other hiking destinations the world over.