When leading on Mt Washington, barring the few I know that regularly work the west side (which we do as well on many occasions), professional guides generally lead groups up the Tuckerman Ravine Trail, hop onto either the winter or summer route of the Lion Head Trail, then get back onto Tuckerman Ravine Trail for the push to the summit before reversing direction for the exit. This is a decent way to go, fairly direct, and the winter route can be pretty exciting since it’s so steep. If the winter route is open, that is. It’s not available until the summer route, part of which is a terrain trap, becomes an avalanche hazard. The downsides to going this way are apparent on the lower sections of the Tuckerman Ravine Trail: it can be crowded being it’s the most-used route, it lacks character with its road-like appearance, and honestly, it’s a bit of a slog. It lacks what many other trails in the White Mountains regularly offer and that is the White Mountains trail experience. But there are other east side options, one in particular is the Boott Spur Trail.

When leading on Mt Washington, barring the few I know that regularly work the west side (which we do as well on many occasions), professional guides generally lead groups up the Tuckerman Ravine Trail, hop onto either the winter or summer route of the Lion Head Trail, then get back onto Tuckerman Ravine Trail for the push to the summit before reversing direction for the exit. This is a decent way to go, fairly direct, and the winter route can be pretty exciting since it’s so steep. If the winter route is open, that is. It’s not available until the summer route, part of which is a terrain trap, becomes an avalanche hazard. The downsides to going this way are apparent on the lower sections of the Tuckerman Ravine Trail: it can be crowded being it’s the most-used route, it lacks character with its road-like appearance, and honestly, it’s a bit of a slog. It lacks what many other trails in the White Mountains regularly offer and that is the White Mountains trail experience. But there are other east side options, one in particular is the Boott Spur Trail.

What is Boott Spur?

Boott Spur, named after Francis Boott, is the 5500′ Mt Washington sub-peak everyone going up the east side admires when they see it for the first time, provided they have views that day. When viewed from near the Lion Head rock formation Boott Spur epitomizes everything alpine. Its steep couloirs, jagged rock, and rugged pitches make an impressive sight to behold. Due to its lack of prominence, however, the peak doesn’t count on most hiking lists as a separate mountain — with exception to a list known as the Trailwrights 72 which recognizes peaks with less than 200 feet (must be 100′ or more) of prominence — but that doesn’t mean it’s not worthy. It can be a destination unto itself.

Boott Spur, named after Francis Boott, is the 5500′ Mt Washington sub-peak everyone going up the east side admires when they see it for the first time, provided they have views that day. When viewed from near the Lion Head rock formation Boott Spur epitomizes everything alpine. Its steep couloirs, jagged rock, and rugged pitches make an impressive sight to behold. Due to its lack of prominence, however, the peak doesn’t count on most hiking lists as a separate mountain — with exception to a list known as the Trailwrights 72 which recognizes peaks with less than 200 feet (must be 100′ or more) of prominence — but that doesn’t mean it’s not worthy. It can be a destination unto itself.

Why We Love It

It’s a little longer summiting Mt Washington that way at 5.19 miles and there is certainly more elevation gain at 4654′ since Boott Spur is its own summit, but these facts are quickly overshadowed by the route’s easier-access rewards: stunning and unique vistas, a real New Hampshire trail character, fewer people allowing for a more intimate mountain experience, an expedited route to treeline — you go up then in, versus in then up — and an exceptional alpine experience. Still want to experience the Tuckerman Ravine Trail and Lion Head? Try making a loop (more on this later).

It’s a little longer summiting Mt Washington that way at 5.19 miles and there is certainly more elevation gain at 4654′ since Boott Spur is its own summit, but these facts are quickly overshadowed by the route’s easier-access rewards: stunning and unique vistas, a real New Hampshire trail character, fewer people allowing for a more intimate mountain experience, an expedited route to treeline — you go up then in, versus in then up — and an exceptional alpine experience. Still want to experience the Tuckerman Ravine Trail and Lion Head? Try making a loop (more on this later).

From start to finish, Boott Spur Trail is a treat. Here’s how it goes:

Route Details

The trails begins four-tenths of a mile up Tuckerman Ravine Trail, at the first switchback just past Crystal Cascade. It quickly crosses the wide swath known as the John Sherburne Ski Trail, then enters the woods turning into a rugged, ledgy trail ultimately reaching a ladder taking one to the ridge crest. It no longer looks anything like Tuckerman Ravine Trail at this point. Now it takes on the character of your typical White Mountains Trail: narrow, rough, pretty. The treadway is rocks and roots, except in winter when like all trails, it fills in and flattens out. It may be a snowshoe mountaineering route depending on the boot pack and snow depth.

The trails begins four-tenths of a mile up Tuckerman Ravine Trail, at the first switchback just past Crystal Cascade. It quickly crosses the wide swath known as the John Sherburne Ski Trail, then enters the woods turning into a rugged, ledgy trail ultimately reaching a ladder taking one to the ridge crest. It no longer looks anything like Tuckerman Ravine Trail at this point. Now it takes on the character of your typical White Mountains Trail: narrow, rough, pretty. The treadway is rocks and roots, except in winter when like all trails, it fills in and flattens out. It may be a snowshoe mountaineering route depending on the boot pack and snow depth.

It doesn’t take long to get to a viewpoint, at a mere half mile in you get a sneak peak of things to come with a great view of Huntington Ravine and Nelson Crag. Soon after this you come to another east-facing viewpoint, or at least that’s what the sign suggests, but it has long since filled in so it’s best to keep going not bothering with this 50-yard spur. The trail flattens then rises steeply once again. During this push you will reach a signed 100-yard side trail on the left leading to a small brook (last water). From there the trail reaches another bulge in the crest and at a mile in you will reach a 25-yard spur trail on the right leading to another, more limited view of Huntington Ravine and the route ahead. Worth the stop, but small and restricted. Back on trail keep heading up the ridge crest passing a few steep and scrambly sections while enjoying a few incidental views that are worth pausing for.

It doesn’t take long to get to a viewpoint, at a mere half mile in you get a sneak peak of things to come with a great view of Huntington Ravine and Nelson Crag. Soon after this you come to another east-facing viewpoint, or at least that’s what the sign suggests, but it has long since filled in so it’s best to keep going not bothering with this 50-yard spur. The trail flattens then rises steeply once again. During this push you will reach a signed 100-yard side trail on the left leading to a small brook (last water). From there the trail reaches another bulge in the crest and at a mile in you will reach a 25-yard spur trail on the right leading to another, more limited view of Huntington Ravine and the route ahead. Worth the stop, but small and restricted. Back on trail keep heading up the ridge crest passing a few steep and scrambly sections while enjoying a few incidental views that are worth pausing for.

At 1.7 miles in, where the main trail takes a sharp left, there is a 30-yard spur to the right leading to “Harvard Rock” and an incredible view of Tuckerman Ravine, Lion Head, and the Summit. Short of being in it, this is one of the best ravine vantage points on the mountain. This is an ideal spot for a break if it’s not too windy — since this outlook is fairly exposed to winds flowing out of the ravine, taking a long, leisurely break here is often not possible, though.

At 1.7 miles in, where the main trail takes a sharp left, there is a 30-yard spur to the right leading to “Harvard Rock” and an incredible view of Tuckerman Ravine, Lion Head, and the Summit. Short of being in it, this is one of the best ravine vantage points on the mountain. This is an ideal spot for a break if it’s not too windy — since this outlook is fairly exposed to winds flowing out of the ravine, taking a long, leisurely break here is often not possible, though.

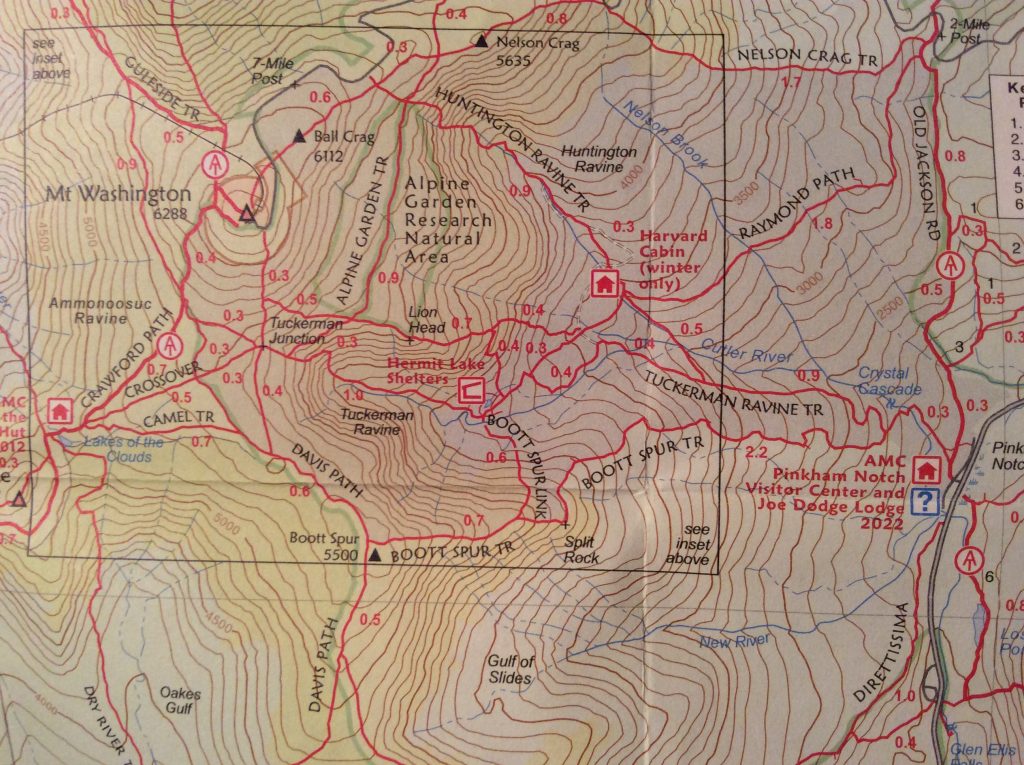

Back on trail hiking for another two-tenths you will emerge from the krummholz and officially reach treeline at a mere 1.9 miles in. The trail then heads towards the Gulf of Slides which is nestled between Slide Peak to the south and Boott Spur and makes for another landmark at two miles in: “Split Rock.” Not to be confused with the so-called keyhole on the Lion Head Trail referred to as Split Rock, the named feature on the Boott Spur Trail actually appears on the map (note it on the AMC map image, above).

Back on trail hiking for another two-tenths you will emerge from the krummholz and officially reach treeline at a mere 1.9 miles in. The trail then heads towards the Gulf of Slides which is nestled between Slide Peak to the south and Boott Spur and makes for another landmark at two miles in: “Split Rock.” Not to be confused with the so-called keyhole on the Lion Head Trail referred to as Split Rock, the named feature on the Boott Spur Trail actually appears on the map (note it on the AMC map image, above).

The trail continues over two minor humps passing through a little more krummholz before reaching a broad, flat ridge and the junction of Boott Spur Link (which drops very steeply to Tuckerman Ravine Trail but isn’t recommended for descent). From here the trail continues climbing up and over one bulge after another until it finally passes just to the north of the actual Boott Spur summit which is marked with a steel Bradford Washburn summit/survey pin. This area, especially the final tenth of a mile just before the summit, is quite breathtaking.

The trail continues over two minor humps passing through a little more krummholz before reaching a broad, flat ridge and the junction of Boott Spur Link (which drops very steeply to Tuckerman Ravine Trail but isn’t recommended for descent). From here the trail continues climbing up and over one bulge after another until it finally passes just to the north of the actual Boott Spur summit which is marked with a steel Bradford Washburn summit/survey pin. This area, especially the final tenth of a mile just before the summit, is quite breathtaking.

Provided the weather is mild enough to continue — since this is a very exposed area — from here the trail drops down to Davis Path where it terminates. To continue on to Mt Washington just stay on Davis Path until you reach the Lawn Cutoff. Taking that will lead you to Tuckerman Ravine Trail at the base of the Washington summit cone. Alternatively you could stay on Davis Path until it reaches Crawford Patch and another, historic way to access the summit (Crawford Path is the oldest continuously used hiking trail in the United States).

Provided the weather is mild enough to continue — since this is a very exposed area — from here the trail drops down to Davis Path where it terminates. To continue on to Mt Washington just stay on Davis Path until you reach the Lawn Cutoff. Taking that will lead you to Tuckerman Ravine Trail at the base of the Washington summit cone. Alternatively you could stay on Davis Path until it reaches Crawford Patch and another, historic way to access the summit (Crawford Path is the oldest continuously used hiking trail in the United States).

To descend you could go back the way you came but we think going down the Lion Head Trail is an interesting way to go, especially if the summer route is still open. If not, if the winter route is open instead, do bring a rope to help with ultra steep sections and know how to use it, 30 meters being sufficient. The final exit is made via Tuckerman Ravine Trail which is far less slog-like going down and you can see what you missed, so to speak.

In Summary

When we go this way we will generally run into single digit numbers of people while on the Boott Spur Trail itself. The trail isn’t mashed down by a snow cat, and we feel it provides one of the mountain’s better non-technical, easy-access alpine mountaineering experiences. Interested in checking it out? If you’re being guided, feel free to request it (on our booking form), though note that it’s not always a good choice because of the weather. That part, though, you can leave to us.