The Cog Railway’s easement on the west side of Mt Washington is heavily impacted – the antithesis of LNT.

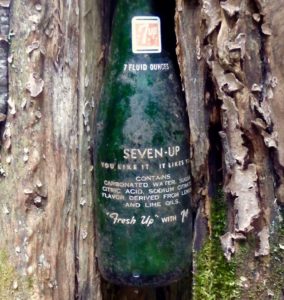

It’s not trash. This bottle “artifact” is treasure.

Photo courtesy of Ellen McDowell Ruggles.

The Magnificent Seven

- 1. Plan Ahead and Prepare

- At first this may seem far removed from the subject of making an impact on the forest and of not leaving traces, but with a little imagination, you might see how some connections can be made. Take, for instance, the hiker without a headlamp, who didn’t plan on needing one, finding him/herself benighted. They did bring a knife and a lighter, though, so proceed to build a tiny cabin in the woods, which by morning gets burned to the ground along with a half acre of surrounding forest. Boom, impact. Okay, we’re really stretching things there to be humorous, but it may fire the imagination a bit.

Photo courtesy Lenka Flaherty.

Let’s consider another hiker, lost with no map or compass requiring a massive search of 100 volunteers. This scenario isn’t nearly so far-fetched; these types of searches are more common than you may realize. Also consider the hiker who didn’t do any research who decides to hike on a trail when it’s muddiest, when it’s most sensitive to damage. Or the hiker who doesn’t bring traction in the spring and has to go off trail and hang from trees to avoid trail ice. Or the hiker who thought that they would need to bring several cans of food, just in case, and end up leaving them for someone else to deal with. Or the hiker/dog owner who failed on planning for the needs of their large, rambunctious puppy or ignorant to the fact that there is no night crew to pick up little green doggy bags.

We’re not meaning to pick on hikers (it’s just what we know best). Please understand that this applies to all sorts of outdoor pursuits in all sorts of places, in all sorts of seasons, such as:

- Water sports at the sea, river, or lake.

- Rock and ice climbing.

- Fishing and hunting.

- Geocaching.

- Canyoneering.

- Snorkeling/SCUBA.

- Winter recreation.

- Even front country activities.

Using your imagination and understanding of these activities, you might be able to see how this principle can apply there as well.

- 2. Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces

- Unlike its more conceptual predecessor, this principle is really more clear, specific, and straight forward. Hike on trails — rock- and root-hop on muddy trails where possible instead of walking through the mud, for example, or spread out your impact on a bushwhack. Also, through this we know not to do things like shortcut switchbacks, create “herd” or “social paths,” widen trails, etc.

For camping, do so in shelters, on platforms, or on designated, previously impacted sites. They say “good campsites are found, not made.” Not to say you can’t make camp by finding a spot in the middle of nowhere, miles from a trail. It’s fine, just disperse your use. Consider getting a hammock!

Also consider this: the closer you are to areas where people congregate, i.e., trailheads, summits, structures (like hut and shelter sites), the more important it is that you concentrate your use to areas already used and authorized within those spaces. Consider these the precariously balanced “Forest Protection Areas” we all know and love.

- 3. Dispose of Wastes Properly

- To better understand the many nuances of this principle, we need to first understand what defines “waste.” Consider this list:

- Food packaging, wrappers, litter, etc.

- Food scraps: crumbs, shells, peels, pits, etc.

- Human/animal feces and urine.

- Toilet paper/hygiene products.

- Soaps, nutrients, gray water, and other products.

Now that we can identify what waste can mean, dealing with it is again for the most part just common sense, albeit there are some “techniques.” There are effectively one of three things we can do with waste, depending on the type: remove it (carry out), bury it, or disperse it. Almost everything gets carried out — know this as the default method as you pack it in — even the crumbs.

Everything else is an exception: feces, for example, is buried in a “cathole” unless you bag it, at which point it must be carried out (“blue bagging it” is a requirement for everyone on glaciers, etc.). Meanwhile toothpaste, gray water, liquid nutrients, and urine are dispersed away from water sources. Pee wildly, fellas, write your name, and spray that toothpaste instead of spitting it out.

- 4. Leave What You Find

- This applies to a few things just as many of the principles do. This one can also lead to some confusion. Most know that if they see some litter that they can contribute to the environment by carrying it out, but the fourth principle is Leave What You Find. A contradiction, yes? Not really. You have to be able to determine if the trash you found isn’t fifty years old or older. That is the only challenge. If it’s a 7-Up bottle from the ’50s stuck in a tree, or an old railroad spike from the logging days, it’s no longer trash. Once it reaches that magical age it, poof, turns from trash to treasure and is considered an “artifact.” And as an artifact it’s protected by law.

Logging camp artifacts.

Of course this applies in other ways. Trundling boulders and felling dead trees is both dangerous and fun, but unless it’s done for reasons of safety, it shouldn’t be done at all. Other examples may including “tagging” — using spray paint, even chalk, to make your mark on the natural world — as well as building “ego cairns” for artistic reasons, making fairy homes, or leaving “kindness rocks.” Let nature be natural. It will change on its own over time. At this point we are bordering on seventh principle territory, keep reading.

Same goes for the spreading of nature, which, for example, is a well established problem with freshwater boaters who trailer their vessels from body of water to body of water. This can potentially spread non-native or invasive species of plants and animals (think watermilfoil and zebra mussels as but two). How else can this apply? Well, we can transport weed seeds and plant matter on our person, in our gear, even in the treads of our boots. If going to another, different location, it’s a good idea to prevent this spread by cleaning these items.

- Continued in next column »

- 5. Minimize Campfire Impacts

- You know what’s an awesome thing to have when camping, right? That’s right: fire. From the s’mores, to the fire’s warmth, to the annual burning of the socks and constantly battling the persistent smoke that seems to waft your way no matter where to sit or stand. But that’s okay. We’ll take it. Having a fire is awesome. It’s romantic and it keeps the bogeyman at bay. What’s not to love?

Of course, you know, LNT is going to have a say. If the wind is blowing in the right direction and not too hard, and you’re prepared to burn it down completely then put out the remainder, and it’s done in an approved, well impacted fire ring, go for it. Try to keep the fire under two feet across and a foot tall and only burn tinder, kindling, and dry deadwood found on the ground with a diameter no larger than your wrist. And watch those socks!

If there is no fire ring or approved, impacted fire pit, the preferred course of action is not to build or establish a fire ring, but to forego the fire altogether and use a stove if cooking or boiling water. (A little Luci lantern is nice for those fireless nights.) There are times, however, when you can still have a fire in an unestablished site:

- Pit/Beach Fire: You may dig a pit at the beach, lake shore, a gravel or sand bar, or really in any gravelly or sandy soil (avoid roots, vegetation, leaves, pine needles, duff, and cryptobiotic or living soil with algae and lichens), and just be sure to burn the fire down completely. Also be sure to remove the ash and disperse it before filling the pit back in. This can be a nice way to enjoy a fire safely since you’ll also have lots of water handy for extinguishing it afterward.

- Mound/Pan Fire: You can build a mound or have a pan fire, but honestly these are both really unlikely and bothersome… and will also involve some heavy lifting. The pan fire is as the name implies. You did bring the large cast iron skillet or roasting pan with you, yes? And as it pertains to the mound fire — having a fire on a mound of gravel or on dirt atop a pad of foil — well, the technique is almost as disruptive as having the fire itself. It just doesn’t seem worth it.

When done with your fire (the one you or someone responsible tended the entire time!), be sure to soak everything, being sure everything is entinguished and fill in the pit, if you had a pit or beach fire. Try to restore the area to its former condition.

- 6. Respect Wildlife

- It’s not just “moose,” it’s Mister Moose! Be respectful. In all seriousness, this is a pretty important principle as failing to respect the wildlife may result in personal injury or death. You could be affected, too! Feeding bears, for example, will lead to habituated bears unafraid of humans. Conflict is inevitable at that juncture. After that you know what happens, right? (Spoiler Alert!) That’s right, the bear almost always dies in the end.

If you like moose, or bears, or you name the animal here, let them be. Enjoy viewing them at a distance and try not to interact. Buy a zoom lens. Don’t allow interaction to happen accidentally, either, by making sure you have good camp craft skills as it pertains to food and waste management. It’s in your best interests, too, especially in bear country.

Photo courtesy of Ken MacGray.

But what about gray jays, you may wonder. Well, Canadian jays, a.k.a. “camp robbers,” make their living by stealing your food. They are opportunists. Officially feeding them is wrong, but the measure of harm in this case may be debated. It is true that feeling their little claws dig into your fingers as they feed out of your hand is neat and that letting them steal food out of your hand is a cool experience. That said, knowing the food they take isn’t eaten but instead stashed, saved for later in the craggy bark of certain nearby trees, this clearly violates the third principle. There’s no way around it if you want to follow the law to the letter, so to speak.

There are also other ways to disrespect wildlife besides directly feeding them or failing to secure your food. Here are some examples:

- Breaking their structures (nests/damns).

- Chasing down/motoring after an animal.

- Failing to control your pet.

- Climbing in nesting sites.

- Entering a sensitive area/time.

As one final thing to consider when venturing into the places where animals live: it’s their home. You’re just a visitor. Ask yourself how you want people to be in your home. Be that way.

- 7. Be Considerate to Other Visitors

- In outdoor leadership school we were introduced to the four basic responsibilities of guides and leaders, by order of importance:

- Minimize risk.

- Minimize impact.

- Maximize learning.

- Maximize fun.

Of these, number two, Minimize Impact, is the one we need to focus on. Never should it be assumed that “impact” relates only to physical impact to the environment as we’ve been talking about. It does relate to it, of course, but it goes well beyond traveling and camping on durable surface as noted in the second principle, too. Respecting Wildlife, the sixth principle, for example, mentions impacts in several other ways. We also can find the effects of impact in the fourth principle, as well since litter is an eyesore and missing artifacts are gone forever.

There’s one other very important consideration when thinking about the word impact: and that is impact to other people. Other hikers, other visitors, others just like you trying to enjoy the same outdoors. Here are a three ways you can minimize impact that haven’t yet been mentioned.

- Limit group size (10 total, anywhere).

- Keep noise down (conversational tones).

- Yield to others (ascenders, smaller groups).

Sure, some will tell you to HYOH (hike your own hike) or, in other words mind your own business, but people aren’t always given that choice.

A Dose of Reality

It’s quite probable that the typical hiker or outdoor enthusiast, regardless of their level of knowledge about the principles of LNT, is going to act selectively. They may, for instance, be great about respecting others and not messing with the wildlife, but be terrible about keeping their fires small or resisting the urge to share with the gray jays. It’s human nature and may very well be the result of stubbornness, obstinance, willfull disobedience, and/or laziness.

It’s quite probable that the typical hiker or outdoor enthusiast, regardless of their level of knowledge about the principles of LNT, is going to act selectively. They may, for instance, be great about respecting others and not messing with the wildlife, but be terrible about keeping their fires small or resisting the urge to share with the gray jays. It’s human nature and may very well be the result of stubbornness, obstinance, willfull disobedience, and/or laziness.

At least, since you’ve read this far, we can rule out ignorance. Now you know.